What Should I Do in a Pandemic? An Essay on Ancestors and Anxiety

The first thing I noticed was the quiet. It was Friday afternoon, a time when the velocity of “busyness” begins to wind down for the weekend anyway. But––I’d already been working from home for a week. There were already “preparations for self-imposed quarantine to flatten the curve” underway. Pandemic anxiety flew high. The store shelves were rapidly emptying, sometimes nonsensically––like people who bought too much toilet paper and no cold remedies. Or, water by the flat as if preparing for a hurricane. Blame our lack of practice; in modern Florida, that’s the only kind of disaster prep we know how to do. Friday evening I stood beneath the blue Spring sky, bright past seven thanks to Daylight Savings Time a week before, and noticed the stilling quiet.

I felt it in my chest first. As an empath, I involuntary collect the energies of those around me like velcro. It reminds me of a video game my nieces and nephew play: Katamari Damacy. The ball starts off small and as it rolls through town, it gathers items and objects onto itself until it’s enormous. That’s what it’s like to be an empath. I pick up tidbits from my family, my children, friends, colleagues, and eventually, strangers in public places, like the grocery store. I feel all my own feelings and then theirs too. Or, parts of them at least––I don’t always get the entire picture. I get bit upon bit so that what I have at the end of the day is a tangled mess of information and reactions that I have to sift through like a wadded ball of yarn I’m determined to unknot because the end result is worth it.

I rather enjoy feeling unknotted. My peace is worth the work it takes to get there.

Last week required more effort than usual to remain calm. To take what I needed from the information sources and leave the rest. To put my boundaries up and armor on so I didn’t empathize to the point of drain and overwhelm. I decided to self-quarantine to protect my asthmatic lungs, curate my news sources, and stick to the basics of self-care during seasons of illness: rest, hydrate, eat well and keep calm. Stress and cortisol weaken the immune system. Then, Friday came.

Friday evening and the quietly blue skies. Friday evening and the slowing vibrations of human activity. My chest unknotted to a depth I hadn’t felt in years without deep meditation and sometimes, marijuana. It felt like the days after 911 when no one flew in planes, no one drove in cars, no one left for work, and for a little while, we as a society got quiet and remembered what truly matters to us in this life. I heard a voice whisper, “It used to always be like this.” The voice came from one of my Grandmothers.

“I’m listening,” I answered.

“What should I do in a pandemic?”

All of my grandmothers and great-grandmothers are dead. And, before you think I’m some sort of weird kook who talks to dead people by candlelight, let me give you a little background.

I was raised Southern Baptist. In that tradition, when people die we hold funerals called “home-going celebrations,” where we set our sadness aside to revel in the thrilled-surety that our loved one is now in heaven with Jesus and we will see them again someday. Raised to take scripture literally, several verses often tripped me up as a kid, and the ones relevant to this explanation were, “thy will be done in heaven as it is in earth,” and, “we’re surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses.”

These verses seemed to merge realms. I wasn’t fond of what I called, “boom-chick” funerals, referring to the boom-chick, boom-chick of the drums at southern gospel funerals. If heaven and clouds of souls and spirits were surrounding us, that certainly impacted what I was being taught about death and eternity. When I converted to Orthodox Christianity, the church expanded on these points. We could pray (talk) to saints and angels: those were the witnesses. Those were the ancestors we were surrounded by and could petition to speak on our behalf to God.

So many faith traditions teach about tapping into the wisdom of our ancestors. They usually aren’t just intercessors and middle-men though: they’re actually wisdom-givers. So, last year, I decided to try it. I sat down at my meditation table, went through my routine of stretches, stillness, and prayers, and asked my ancestral guides to reveal themselves to me. Who are you? Who’s paying attention to my life here? Who has life-experience and wisdom to offer?

Friday I asked, “What should I do in a pandemic?”

This time, the answering voices have been my grandmothers and great-grandmothers. When the worries are writing-related, I ask my literary guides. When they are about something that scares me, I ask the protectors. Sometimes I ask my daughter; sometimes I ask the seven archangels, whom I’ve learned to call by name. Whatever the worry is, there’s always a wise and comforting voice nearby.

Why not just Jesus? Well, because his human life was that of a thirty-something single male in an ancient society, and that perspective isn’t always the one I need. And why not just God? That’s a big question and an idea that’s ever-expanding for me. I suppose in conversing with voices who are helping me produce good fruit in my life, I am participating in asking “God.” I’m asking eternity. I’m asking Love.

“What should I do in a pandemic?”

The news media kept drawing a parallel between COVID-19 and the Spanish Flu of 1918. That year all of my great-grandmothers were parents. My grandmothers would soon be born––and on my mother’s side, the egg that would make my mother would grow inside my grandmother’s tiny womb, inside her mother, who was raising a family during the pandemic of the Spanish Flu in 1918.

World War 1 had just ended. Alcohol was illegal. Model T’s were spreading but not yet common. Movies were silent and so were women: they couldn’t vote yet or use birth control. Information flowed slowly and wartime censors muted news of the flu to keep morale up. The troops were coming home. Democracy was saved.

But death was all around them. Pregnant women were the most likely to die and if they lived, 26% of them lost their babies. Obituaries for dead soldiers paralleled deaths from the flu in the newspapers. So many families had their sons and brothers survive the war only to die from flu at home. There were also deaths from typhoid, yellow fever, Diptheria, and cholera all around them. Nobody knew it at the time, but when the then-Surgeon General increased the recommended dosage of Aspirin to treat the flu, 33% of all deaths were due to aspirin poisoning.

Can there have been a more frightening time to be a mother in modern times? I feel like anything my great-grandmothers learned from that would be useful to me.

I can tell you my ancestors hardly know how to make sense of the amount of time I spend gathering information. For one thing, not all of the information I gather is of any good. “What are you going to do with that?” I hear her say, in response to a procession of memes. “Pshaw. Go put some beans on,” she says, getting up to leave. Visiting ancestors only stay as long as someone is listening. If there’s one thing every single one of my grandmas and great-grandmas had in common is that they refuse to suffer fools.

“Keep calm and carry on” means keep your hands busy.

Making food with ingredients, usually, three times a day is something my great-grandmothers did. Additionally, they baked bread and mended clothes. They hung laundry on clotheslines, including diapers. I know from my own babies how meditative hanging diapers on the line can be. There’s a sacred rhythm to housework and homekeeping––and tremendous anxiety relief. When my children were small and we were so poor I often had to make a decision between milk and toilet paper, I tapped into the wisdom of my great-grandmothers and depression-era grandmothers and self-employed creative parents to provide for my children. It worked.

I learned to garden. I figured out how to live without toilet paper. In books, I learned how to make my own laundry detergent and ferment yogurt. Every house I ‘ve lived in has had a clothesline. I know how to can and preserve food. These skills all came in handy when we panic-prepared for Y2k. They’ll undoubtedly come in handy again, maybe during this pandemic. Spanish Flu lasted from 1917-1920. COVID-19 could last a few years too.

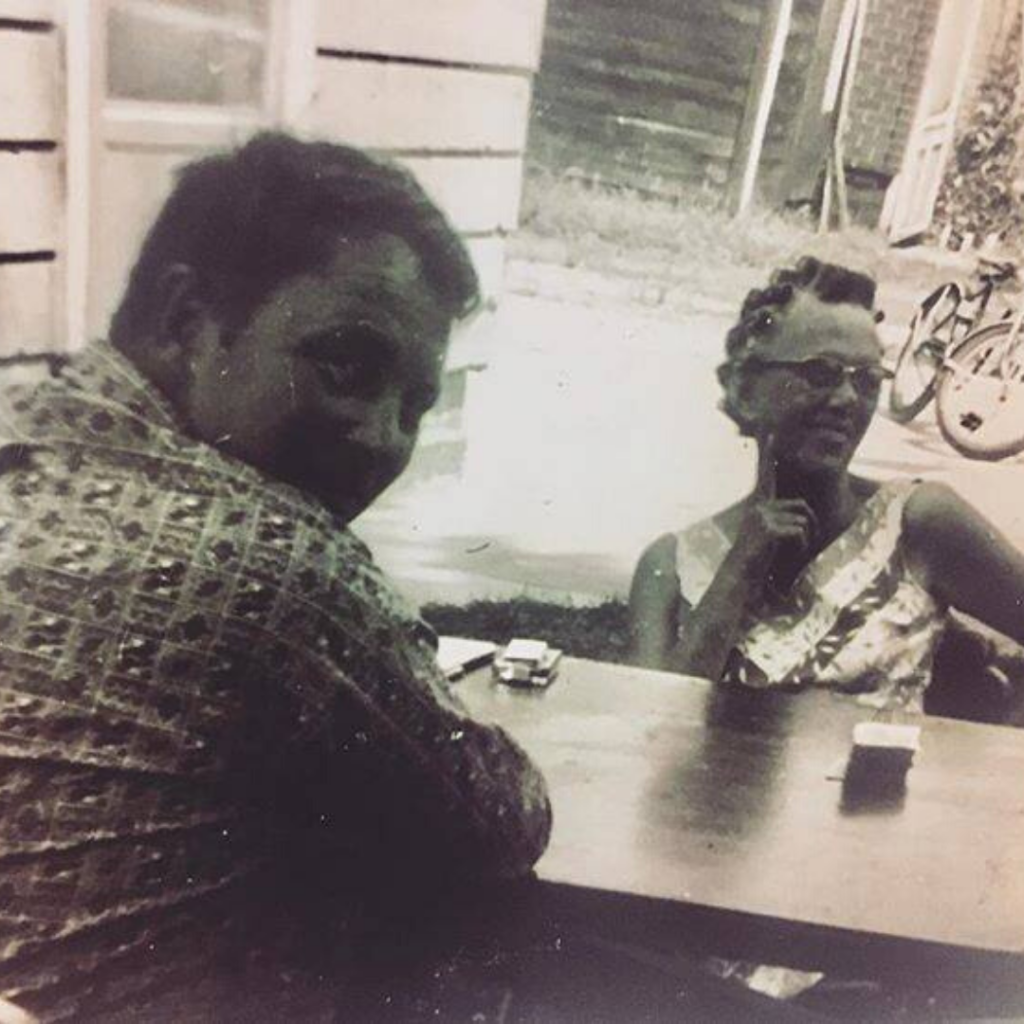

When I knew them, as a young child, my great-grandmothers had an easier life than when they were new parents. I only remember one of them. Their surviving children were grandparents themselves. By 1974 my grandmothers were older women still with decades to go in this life. Easier lives meant leisure time. They kept busy playing cards, smoking cigarettes, working puzzles, endlessly crotcheting blankets. Their cooking demands shrank to smaller quantities. One of my great-grandmothers had a house in Florida with a sand yard that needed to be raked. A pandemic hadn’t happened in so long the Spanish Flu was called a “forgotten pandemic.” Life moved on.

Their point, the one they repeatedly and collectively make to me, is to focus on practical work more. To feel the quiet more. To fret and investigate less. That’s what you do in a pandemic. That’s how you calm nerves and anxiety (Also––meds and marijuana, I interject. No use in ignoring the wisdom of our day, Grandma. She nods and smiles). Doing the next right thing, over and over, is how you keep calm and carry on.

“Go put some beans on,” she says. She means “to soak,” because dry beans are cheap and feed a lot of people well. You have to think about them in a day in advance of when you want to eat them and once they’re on the stove, you have to stay home and be present enough to monitor them. They’re also lenten, which season it is, and nourishing, which people protecting their immune systems need.

It’s possible deaths are going to be all around us again. “What did you expect,” says one of my great-grandmothers with a sad shrug and a pull on her cigarette. She’s sitting near me under the trees because I’m out here marveling again at the quiet sky. “Why not ask your kid to play cards,” she says. I understand her position isn’t cavalier––she lived through too much for that. Her attention reflexes to what’s in her control and she encourages me to do the same with mine. “You’ve got life good, kid,” she mutters. She’s right. I do.

In 2020 we have unprecedented hygiene, medicine, health care, understanding, communications, and connection. I don’t have to add handwashing the family’s laundry and mending to my list of things to do. We’re unlikely to need mass graves dug with machines. I have a job and on Friday, I voted.

On Saturday I watched videos online of Italians in quarantine singing to each other from balconies. Our city’s orchestra held a live concert and streamed it. I spoke with all of my children and my mom on the phone. Maybe art and humanity are what also gets us through this. I went into the kitchen and turned on the light. From the Corona-stocked pantry, I took a bag of white Great Nothern beans and thought about how many steps were ahead. “Wisdom, let us attend,” we hear each Sunday when they read from the Bible. This was the Gospel According to Grandma. I poured the beans into a white ceramic bowl and covered them with clean water right from the faucet and set them to soak.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.